I have Chinese porcelain recovered from three shipwrecks: the Ca Mau Cargo, the Nanking Cargo and the Tek Sing Treasure. These three wrecks carried porcelain mainly from the years 1725, 1750, and 1820 of the Quing dynasty (1644 to 1912), the last imperial dynasty of China. Rather than giving a precise year of manufacture it is the custom to attribute Chinese pottery to an imperial reign and the reigning emperors for those years were Yongzheng (1733 to 1735), Quianlong (1736 to 1796), Jiaquing (1796 to 1820), and Daoguang (1821 to 1850). Strictly speaking one should say, for example, Yongzheng Emperor (and never Emperor Yongzhen) for these are era or reign titles, not personal names.

These are possibly the last great shipwreck cargo recoveries since all such seabed excavations, other than officially state sponsored ones, are now banned under the provisions of the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The treaty was adopted on 2 November 2001 by the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The convention is intended to protect "all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character" which have been under water for over 100 years.

China now claims all shipwrecks in the South China Sea.

The Ca Mau Cargo

In 1998 Vietnamese fishermen snagged their nets on the wreck of a Chinese junk near Ca Mau in southern Vietnam. The ship, an ocean going junk, probably sank around 1725 en route from Canton (now called Guangzhou) to the Dutch trading port of Batavia (Jakarta) in Indonesia. About 130,000 ceramics from this wreck were salvaged from the seabed; some pieces bear the four or six-character mark of the Qing emperor Yongzheng, regnant between 1723 and 1735 (lots 109-111). This establishes an ante quem date for these objects: they cannot have been made before 1723 when Yongzheng succeed his father, Emperor Kangxi, who reigned from 1662 to 1722. The bulk of the cargo, mostly tea bowls and saucers, was destined for Europe, but some was intended for Asian markets. More details of the Ca Mau wreck at the National Museum of Australia here

The bulk of the Ca Mau porcelain was made in about 1725 in Jingdezhen in southern China. From there it had to be transported to Canton along a hazardous route which started from Lake Poyang and proceeded up the Gan River to Nanchang. There it had to be re-loaded onto smaller river boats, the porcelain cargo would then be hauled against the current, upstream to Ganzhou (122 meters above sea level). Continuing on smaller rivers, the cargo boats eventually reached the southern border of Jiangxi province. Here the porcelain had to be unloaded and carried on bamboo poles over the Dayu Mountains (a part of the larger Nan Mountains system) across the Meiling Pass; a broad but steep and difficult stretch of about 30 kilometers that peaks at about 275 meters above sea level. On descending from the pass the porcelain was re-loaded onto sampans that navigated the winding narrow upper reaches of the Bei Jiang River before finally reaching Canton. There it was ferried by sampans to the ships anchored down river. It was a difficult and time-consuming journey of about 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) and it took about five months of hard work to fully load a ship with porcelain and tea.

There is more information on Jingdezhen in an excellent article by Sten Jostrand here.

1.

Ca Mau saucer - Lot 41510

Diameter: 99.3mm, height: 18mm, base diameter: 61.6mm, weight: g.

2.

Ca Mau Cargo Saucer - Lot 41525

Diameter: 99.5mm, height: 19.8mm, base diameter: 61.3mm, weight: g.

2.

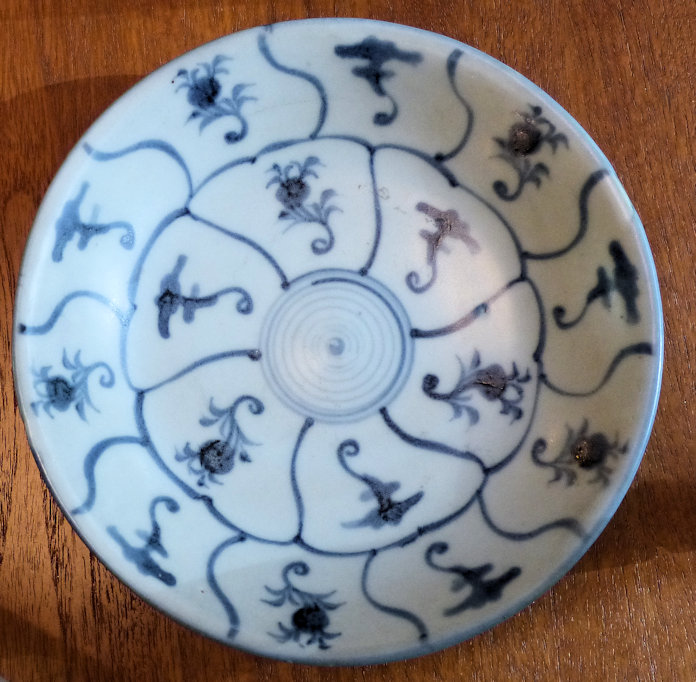

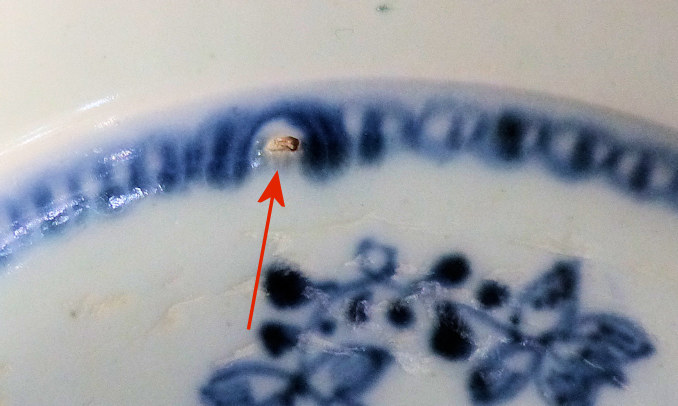

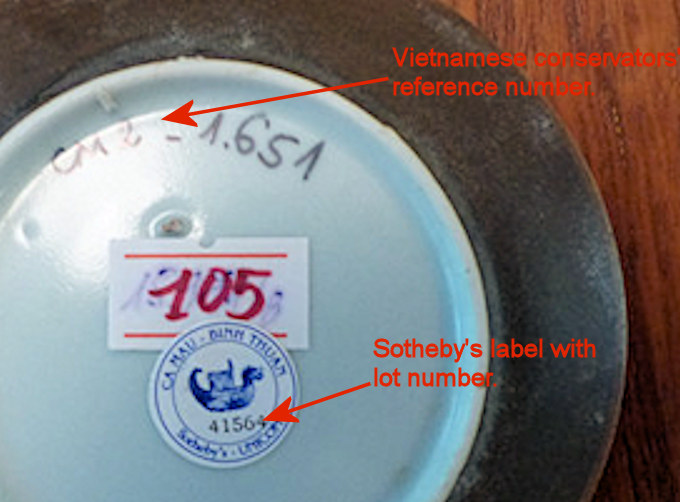

Ca Mau Cargo Saucer - Lot 41564

Diameter: 99.7mm, height: 17.7mm, base diameter: 61.4mm, weight: g.

2.

Ca Mau Cargo Porcelain Box

Base diameter: 66.4mm, base height: 19.8mm, lid diameter: 66.9mm, height with lid on: 39.2mm, weight: g.

2.

Ca Mau Cargo Porcelain Box

Base diameter: 65.8mm, base height: 20mm, lid diameter: 65.3mm, height with lid on: 39.6mm, weight: g.

The Nanking Cargo

Strictly speaking it is the Geldermalsen's cargo. The Geldermalsen was a big cargo ship belonging to the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch East India Company, one of six ships that were commissioned for the Zeeland division of the Dutch East India Company. The VOC kept accurate records many of which have survived and, thanks to the meticulous research of Professor C. J. A. Jörg, we know a great deal about this ship.

It was commissioned on 5 September 1746 by the Directors of the Zealand Chamber along with five other ships. For this particular one of the directors, Jan van Borssele, was asked to choose a name; he did not deviate from the custom of using the names of personal country-seats or estates for VOC ships and he named the East Indiaman after the manor Geldermalsen owned by his family. Construction began the following month under the direction of Hendrick Raas.

The ship was 42 feet (12.8m) wide and 150 feet (45.72m) long; it was delivered to the VOC on 10 July 1747, making her maiden voyage to the Indies on 16 August 1748, captained by Willem Mareeuw van den Hoek, arriving at Batavia on 31 March 1749.

Subsequently she left for Japan on 21 June, arriving on 2 August, and returning to Batavia on 31 October where she arrives on 10 January 1750.

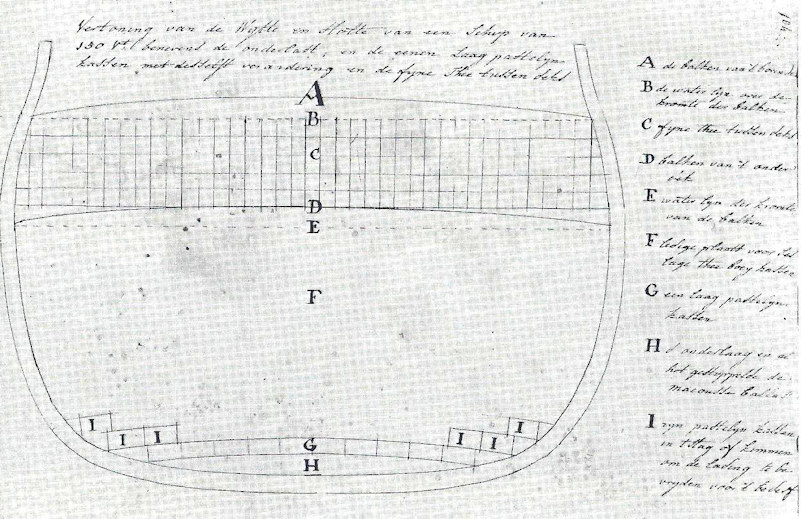

Via Cheribon (March 1750) and Bantam (April) the Geldermalsen is now directed to Canton to take goods to Surat. That, again, is quite a voyage and in China it takes months to collect the proper merchandise.It took five months to load the Geldermalsen for her last fateful voyage. Her principal and most valuable cargo was tea, not porcelain. Porcelain was profitable, with a profit yield of 75 to 100 per cent at the quayside auctions in the Netherlands, but it also served as ballast and its crates formed a very flat base for the crates of tea which were placed on top. A contemporary sketch has survived showing how this was achieved:Finally, the Geldermalsen leaves for Gujarat where she arrives on March 8, 1751, after having successfully warded off an attack by pirates off the coast of Goa. Once more loading and unloading, departure on April 15. Via Cochin and Malacca the ship sails back to Canton, where on July 21, 1751, the Geldermalsen can join the other ships of the VOC who are waiting there to be loaded.

.... The Geldermalsen's new destination is the Netherlands. A new crew comes on board; mostly they have come along on the Standvastigheid from Batavia. The new captain is Jan Diederik Morel ...

The Geldermalsen History and Porcelain, Jörg, 1986, page 41.

It was the tea that in this wreck and the other wrecks preserved the porcelain in prime condition for centuries on the seabed. As the wooden chests of porcelain and tea disintegrated without trace the tea formed a massive protective cover several meters thick over the porcelain; porcelain not under the tea became encrusted with marine growth and coral.

The Geldermalsen set sail from Canton on 18 December 1751. At about 7 PM on Monday, 3 January, 1752, she crashed into a reef in the South China seas and sank, and there the Dutch East India man lay until discovered by Mike Hatcher and Max de Rham in 1985.

The best account of the salvage operation is given in The Nanking Cargo written by Antony Thorncroft, published by Hamish Hamilton, London, 1987 and there is some additional information here.

There were some interesting variations in the prices, especially among the cheapest items the Batavian ware bowls, brown on the outside and with a bamboo and peony pattern on the interior. The less affluent buyers were bidding furiously against each other for the smallest sized lots of twelve bowls and saucers; they sold at the start for 4,500 guilders, against a top pre-sale estimate of 600 guilders. With buyers commission of sixteen per cent added on, it worked out at roughly £100 [£279 in 2017 values] or slightly more for each bowl and saucer.The Chinese government sent two experts on Chinese porcelain to the auction in Amsterdam and Christies gave them bidding paddle number one as a courtesy. Unfortunately, the Cultural Revolution had crippled the economy and china had not fully recovered by 1986. With only $30,000 they couldn't even afford the opening prices for any of the lots and left empty handed.But, a dozen or so lots later, forty-eight bowls and saucers in groups were going for sums which brought the unit price down to under £30 a set [about £84 today]. The price stayed at roughly this level for the lots of seventy-two sets, but the real bargains were claimed by the dealers competing for lots with a hundred and forty-four sets - by now the unit price was around £20 [£56]

The Nanking Cargo by Antony Thorncroft, Hamish Hamilton Ltd, London, 1987, page 117.

Return

1.

Nanking Treasure - Teabowl and saucer - Lot 5707

The chrysanthemum rock pattern in blue and enamels. Teabowl and saucer painted with chrysanthemum, bamboo and daisy issuing around a jagged outcrop of blue rockwork, below a band of trellis-pattern. Wafer thin and transparent; about 90 per cent of the over-glaze enamel has survived. Jingdezhen circa 1750.

Tea bowl diameter: 87mm, height: 47.6mm, base diameter: 39.6mm, base depth: 6.3mm.

Tea saucer diameter: 133mm, height: 26.5mm, base diameter: 81.8mm.

Return

Return

2.

Nanking Treasure - large bowl - Lot 3015

Christie's auction catalogue for lots 3001-3019, which includes this bowl, is as follows: THE 'SCHOLAR ON BRIDGE PATTERN' IN BLUE AND ENAMELS, LARGE SIZE. CHINESE IMARI BOWLS painted with a scholar crossing a bridge between two rocky islets with a pavillion and retreats beside pine on the exterior, circa 1750.

These large blue and enamal bowls are relatively rare, only 458 were recovered. In contrast, there were 13,270 Batavian blue pine pattern cups and 10,910 matching saucers.

Bowl diameter: 190mm, height: 85.7mm, base diameter: 95.4mm, base depth: 15.2mm, weight: 575g.

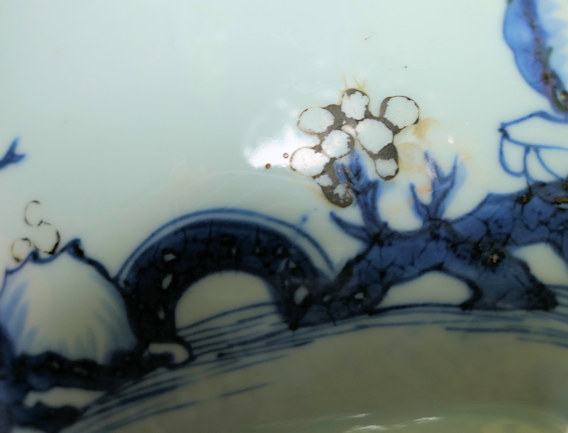

On my bowl 'the scholar crossing the bridge' is no longer visible as the seawater has desolved the over-glaze pigment. However, the outline of his figure remains, evidently drawn on the unfired bowl before the paint was applied, as does the outline of the bridge parapet and also the criss-cross pattern at the top of the inside of the bowl, but they can only be seen in oblique lighting. In the second photo in direct light showing the whole bridge the scholar and bridge parapet are invisible. The third photograph shows only a small section of the inner criss-cross pattern caught in oblique light, but the pattern is continuous all around the rim and shows wherever oblique light strikes it. Of course I would have preferred to have had the full painted figure, but on the positive side this seawater damage provides a guarantee of absolute authenticity as it would be extremely difficult for a forger to duplicate these hidden features and, even if possible, not worth the effort.

Here is an example of 'the scholar crossing the bridge' pattern on a similar Nanking bowl:

The Tek Sing Treasure

The detail that Nigel Pickford has managed to accrue from widely scattered sources is quite astonishing:

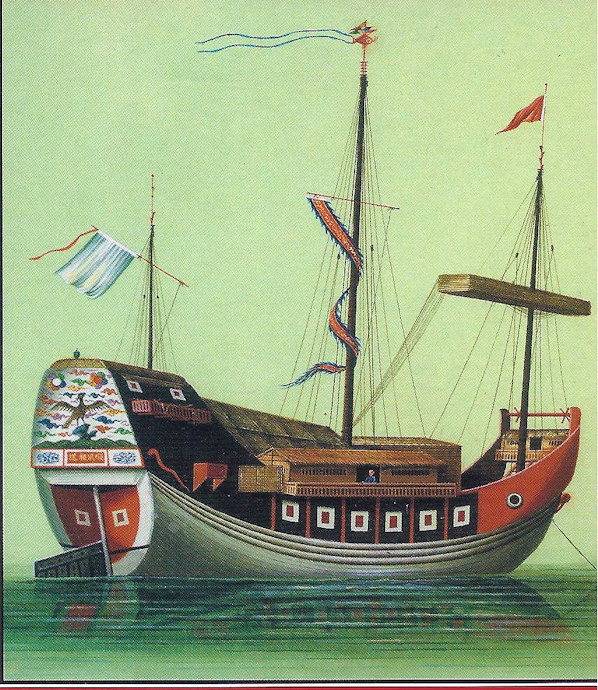

In early January 1822 a large ocean-going junk, fat bellied, with squared-off bows and stern rising high out of the water, was lying calmly at anchor in Amoy harbour. On the stern was painted an iridescently coloured, long-necked bird with an elaborate tracery of foliage. At the prow end were depicted the two huge, ever-watchful oculi that all sea-going junks were adorned with - staring eyes constantly scanning the horizon for any signs of danger, part of a grotesque visage designed to frighten off sea deamons. The bows were painted green, which signified that the junk belonged to the port of Amoy, and they also carried the junk's identifying registration in bold red characters.'The Legacy of the Tek Singh: China's Titanic - the Tragedy and its Treasure' by Nigel Pickford & Michael Hatcher, Granta Editions, Cambridge, 2000, page 13.

Amoy is now known as Hsiemen and the junk at anchor there was bound for Batavia, modern Jakarta. The Tek Sing's length was about 60 meters and she was divided into fifteen watertight compartments by means of transverse bulkheads; a safety measure common in Chinese junks since the fourteenth century but not adopted by Western shipbuilders until the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike the Geldermalsen the Tek Sing's cargo of tea and porcelain was not intended primarily for the European market but would have been loaded in the same way over a period of months, the porcelain at the bottom acting as ballast and the tea crates stacked directly above it. In addition, on this particular voyage she carried some 1,600 men, women, and children, aged between 6 and 70 but mostly men of working age, poor emigrants seeking work abroad; in total, with a crew of 400 skilled and unskilled hands, there were about 2,000 people crowding this ship on her last fateful voyage.

The Tek Sing weighed anchor on 14 January 1822 (according to Nigel Pickford; Hugh Edward in his book Treasures of the Deep), page 257, states she left Amoy "in December 1821"); be that as it may, both are in agreement that she was captained by Io Tanko, an experienced seaman, and that, for reasons unknown, he had deviated from the usual junk route to Batavia and on the evening of the 5th of February the Tek Sing had struck on a reef in the vicinity of Belvedere Rock about twelve miles NNW of Gaspar Island and sank in 120 feet of water. Of the 2,000 on board there were only 150 survivors, a greater loss of life than that of the Titanic. And there she lay undisturbed until salvator Captain Mike Hatcher discovered her in June 1998.

Captain Mike Hatcher and his team recovered a vast amount of porcelain, several tons amounting to some 360,000 pieces, which was auctioned by Nagel Auctions in Stuttgart, Germany, in 16,100 lots from Friday, 17 November, to Saturday, 25 November 2000. The bulk of the Tek Sing porcelain came from an area of production centred upon the town of Dehua in Fujian province, to the south of Jingdezhen in Jiangsi province, and was produced in, or before, 1821. (On eBay, Tek Sing porcelain is usually dated 'circa 1822', but that cannot possibly be right.)

Return

1.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 46 B Lot 1113

Blue and white circular bowl of lotus form painted in two concentric bands of petals around a central spiral with alternating lingzhy-fungus and fruiting peach, the exterior with similar decoration.

The lingzhi is the sacred fungus of immortality, considered by the Daoist mystics as the food of the Immortals. Symbol of longevity, since when dry it becomes extremely durable.

The peach is the emblem of marriage and symbol of immortality and of springtime. The Daoists consider it a sacred fruit.

Diameter: 158mm, height: 64mm, base diameter: 78mm, bowl depth: 52mm, weight: 375g.

Return

Return

2.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 46

Diameter: 156mm, height: 64mm, base diameter: 68mm, bowl depth: 52mm, weight: 350g.

Return

Return

3.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 46 Lot 8049

Diameter: 154mm, height: 70mm, base diameter: 73mm, bowl depth: 53mm, weight: 375g.

Return

Return

4.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 227

Swatow slightly distorted circular bowl with slightly fluted side originally painted over-glaze in yellow, green and iron-red on the white ground with a band of aster half-flower heads alternating with trellis design above a band of lotus petals; the interior was painted with a lotus bloom which has all but disappeared as has much of the enamel.

The lotus is symbol of purity, the emblem of July and of summer, and sacred flower of the Buddhists.

Diameter: distorted oval shape 151x159mm, height: 73mm, base diameter: 73mm, bowl depth: 54mm, weight: 350g.

Return

Return

5.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 45 B Lot 15997 (one of 24 in this lot)

Blue and white circular saucer of lotus form painted in two concentric bands of petals around a central spiral with alternating lingzhy-fungus and fruiting peach, the exterior with similar decoration.

Diameter: 181mm, height: 38mm, base diameter: 97mm, plate depth: 30mm, weight: 350g.

Return

Return

6.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 45 D Lot 15971

Diameter: 180mm, height: 36mm, base diameter: 105mm, plate depth: 31mm, weight: 350g.

Return

Return

7.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 45 TS 45 B Lot 15997

Diameter: 186mm, height: 38mm, base diameter: 104mm, plate depth: 25mm, weight: 350g.

Return

Return

8.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 151

Diameter: 176mm, height: 31mm, base diameter: 108mm, plate depth: 22mm, weight: 275g.

Return

Return

9.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 80 A Lot 5675

Blue and white saucer dish with slightly flared side painted in the centre with reeds issuing from rockwork between bamboo and a flowering peony plant, the underside with three floral sprays and the base with a Chinese two character mark within a double ring.

Bamboo is the emblem of longevity and a Confucian symbol of eternal friendship. The peony is considered the queen of flowers, symbolising Spring. In the Chinese South it isconsidered the flower of love, affection and femminine beauty. Sometimes synonimous with wealth; a harbinger of good luck.

Diameter: 150mm, height: 33mm, base diameter: 91mm, plate depth: 23mm, weight: 200g.

Return

Return

10.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 205 C Lot 5115

Small circular saucer covered on the upper surface with anolive glaze stopping short of the rim; with coral accretions.

Diameter: 90mm, height: 20mm, base diameter: 43mm, plate depth: 19mm, weight: 50g.

Return

Return

11.

Tek Sing Treasure TS 94 Lot 13832

Blue and white circular plate painted in the centre with a flowering peony spray amongst blooming prunes and other sprays, all within a band of contiguous n an u shaped pattern and another of dots and criss-crosses on the rim.

Prunus, one of the 'Three Friends of Winter'. Wild flower, symbol of Winter, corresponding to January. It is also the emblem of beauty, purity and longevity, for it is believed that Laozi, the legendary Daoist philosopher, was born under its branches. It is the Chinese 'National Flower'.

Diameter: 210mm, height: 48mm, base diameter: 104mm, plate depth: 32mm, weight: 500g.

The Dutch seemed to have favoured infusing tea in the teabowl then drinking it from the saucer. The English, fourth painting, seemingly drank directly from the teabowl.

Imari ware, not shipwreck recovery items

12. Japanese Imari

The Shichifukujin, the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan. The central figure in the foreground is the godess Benzaiden accompanied by her white snake. She is the only female fukujin in the group of seven. Godess of everything that flows and patron of artists, dancers, and geishas, amongst others. She is also known as the White Snake Godess of Japan.

More detail on the Japanese gods here.

Diameter: 182mm, height:23mm, base diameter: 109mm, plate depth: 14mm, weight: 300g.

Return

Return

13.

Chinese Imari

Diameter: 209mm, height: 21mm, base diameter: 116mm, plate depth: 11mm, weight: 375g.

Return

Return

14.

Chinese Imari

Diameter: 154mm, height: 31mm, base diameter: 84mm, plate depth: 18mm, weight: 200g.

One of the many attractions of collecting shipwreck pottery is the assured provenance of all recovered items, usually government backed and auctioned by highly reputable auction houses (Christies, Nagel, Southeby, etc). In contrast, it has been estimated that over 99 per cent of Ming and Qing porcelain is fake, particularly from Chinese vendors. The Chinese government prohibits the export of any item over 100 years old.

Here's an item I saw recently on eBay; the label on it is quite meaningless, even the ship on this label is not a Chinese junk. It was offered with a 'Certificate of Guarantee':

Here are some links to guidance on fakery:

Detecting fake Chinese porcelain

Gotheborg; fakes

Nanhai Marine Archaeology on fakes

Fakes